Advanced Research Students Unveil Professional Research Findings

Titanium alloy debris released by magnetically controlled growth rod treatment for scoliosis does not appear to have a negative effect on bone growth. Leptospirosis in Thailand follows a significant annual periodicity, with cases peaking during the rainy season of August and September. Organoids with mutated RING1 genes have more stem cells and fewer differentiated cells, which might explain why RING1 mutations can cause microcephaly. When cars make left turns, they slow to turning velocity but then speed up during their turn, which contrasts with the currently accepted turn speed profile. Computer programming and machine learning can come together to perform retroradiosynthesis, improving the efficiency of manufacturing radiochemicals for use in PET scans. And the SPEAR software program is capable of successfully mapping and editing sound spectra.

What — you didn’t know?

Well, you would if you’d followed Greenhills’ Advanced Research Program. Seniors who participated in the program presented these findings, and many more, at the program’s annual showcase Monday night. As always, even faculty sponsor Julie Smith was blown away.

“It is really phenomenal,” Smith said. “I think I have the best job in the school, because I get to learn so much every year with the projects that my students are doing.”

The Advanced Research process begins with the application, which is due at the end of the first semester of junior year. Once students have officially joined the class, they work with Smith to refine their research questions and find a research host. This year, research hosts included the University of Michigan, Michigan Technological University, the University of Toledo, Saginaw Valley State University, Mount Sinai Cleft and Craniofacial Center, and the University of South Florida. Other notable past hosts have included California Institute of Technology and Ford Motor Company.

The summer before senior year begins, students work with their research hosts to conduct professional-caliber studies. They write procedures, find subjects, gather data, and follow analysis plans. Often, the process lasts for months after the summer research period ends. Professional research, after all, takes time.

The summer before senior year begins, students work with their research hosts to conduct professional-caliber studies. They write procedures, find subjects, gather data, and follow analysis plans. Often, the process lasts for months after the summer research period ends. Professional research, after all, takes time.

Senior Jeremy Kovacs, for instance, worked with the University of Michigan Department of Radiology to revolutionize the way chemicals for use in PET scans are manufactured. PET scans utilize radiolabeled molecules manufactured from ordinary molecules and radioactive isotopes. Kovacs wrote a computer program that can examine an input molecule and output the various bonding sites for radioactive isotopes, as well as which potential radiolabeled molecule each bonding site will create. Combined with a program written by a University of Michigan student in the same lab that can predict the reactivity of a given radiochemical, an important metric for PET scans, Kovacs’ is an important step forward for medicine, and a genuine new discovery.

“When someone has a PET scan, they have to manufacture those radiochemicals that morning, so that they can be used in the PET scanner later in the day,” Smith said. “If they can find an efficient way to do that — which is what his code is doing — that has the implication to change a huge part of medicine.”

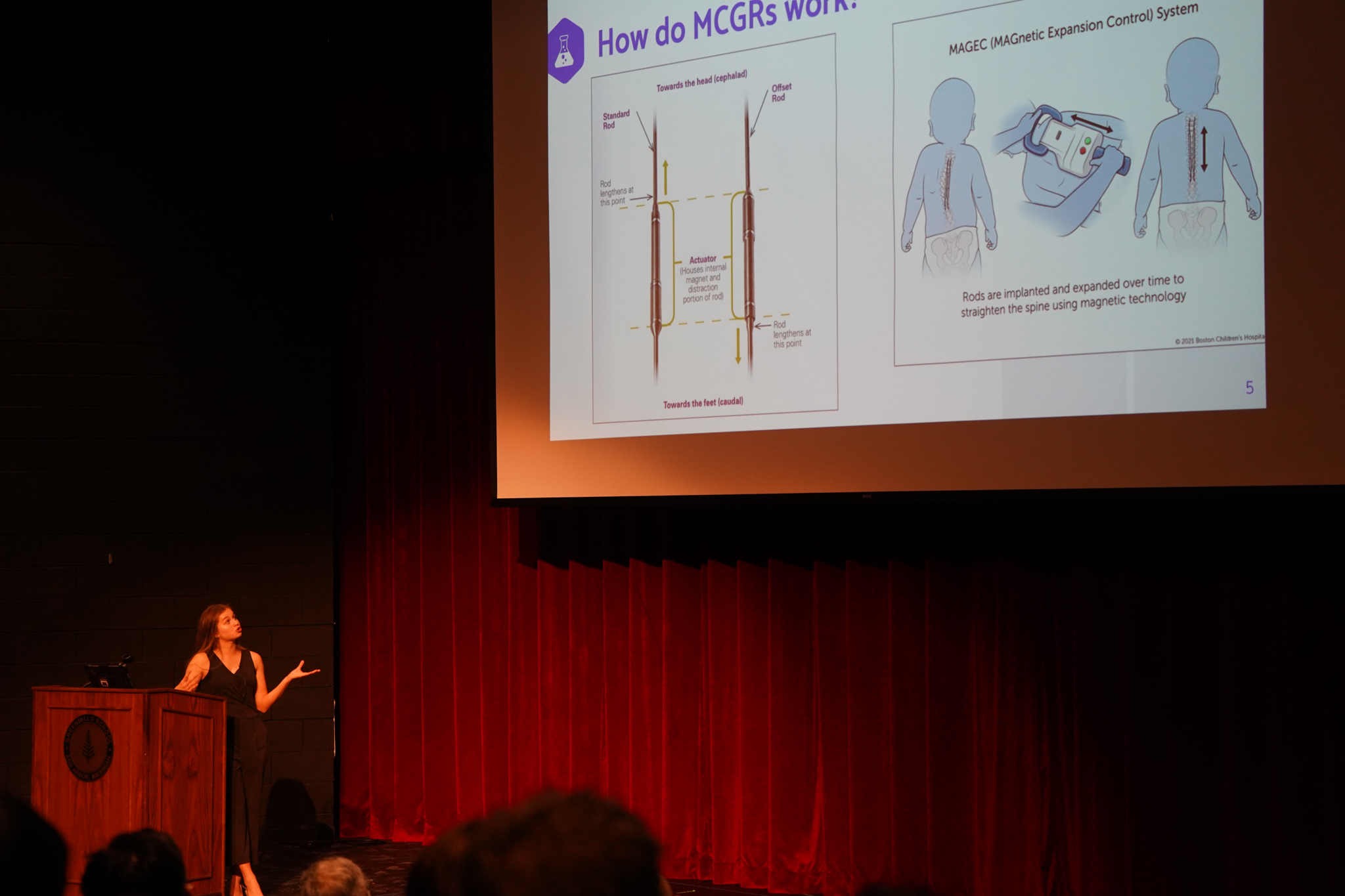

Another Advanced Research student, Monica Behrend, studied magnetically controlled growth rods (MCGRs), a new treatment for early-onset scoliosis. Right now, children with scoliosis are treated with rods that straighten the spine, but the rods need constant surgical replacement as the children grow. MCGRs, on the other hand, do not require surgery to lengthen, but can be adjusted externally using magnetism. The only problem with MCGRs is that they’re made from titanium, and as the rods lengthen, friction causes them to shed small amounts of titanium debris.

Another Advanced Research student, Monica Behrend, studied magnetically controlled growth rods (MCGRs), a new treatment for early-onset scoliosis. Right now, children with scoliosis are treated with rods that straighten the spine, but the rods need constant surgical replacement as the children grow. MCGRs, on the other hand, do not require surgery to lengthen, but can be adjusted externally using magnetism. The only problem with MCGRs is that they’re made from titanium, and as the rods lengthen, friction causes them to shed small amounts of titanium debris.

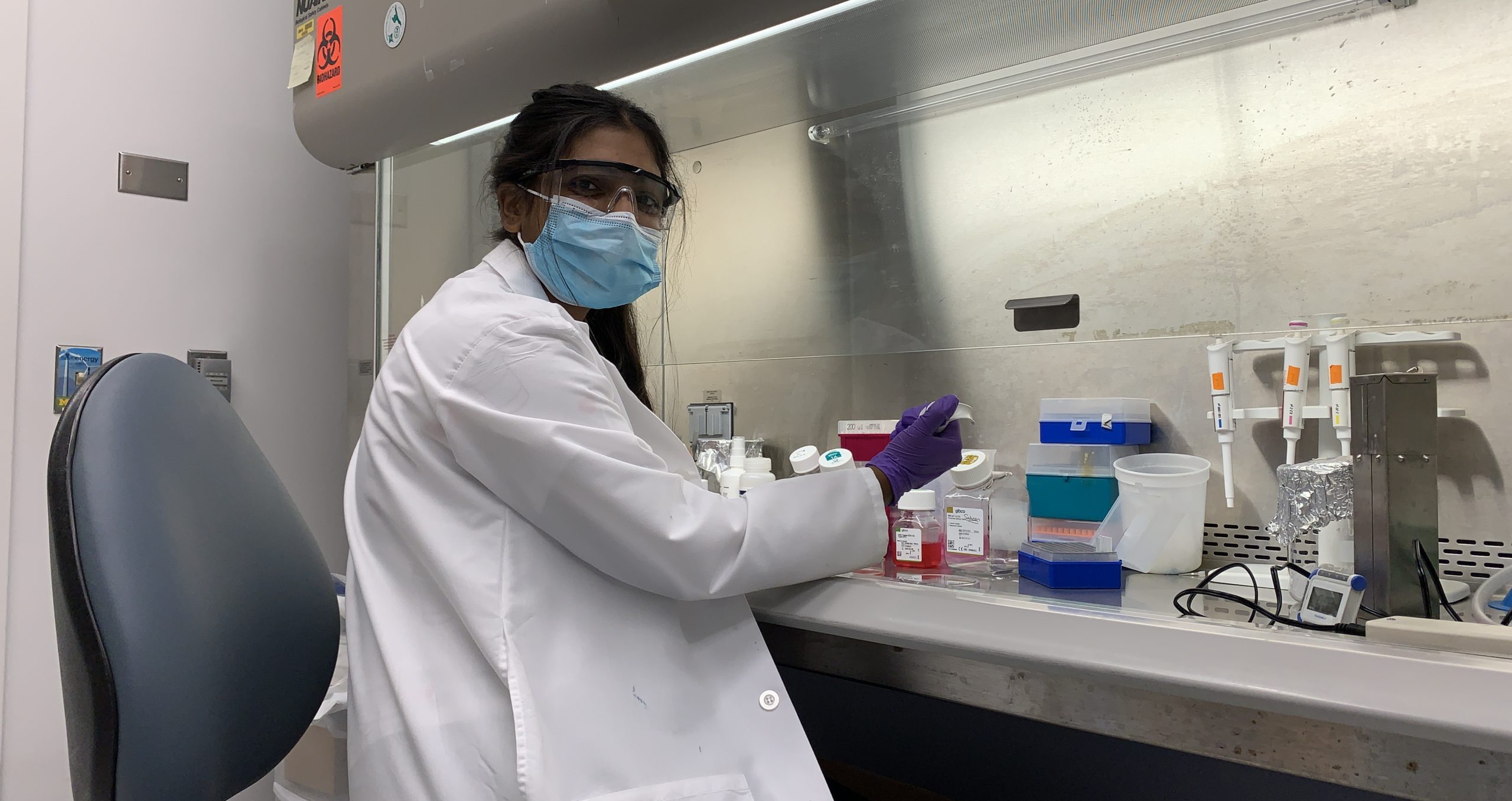

To test whether the titanium debris negatively impacted vertebral bone growth, as some researchers worried it might, Behrend studied three groups of mice, one implanted with titanium debris and two control groups. At 12 weeks old, the spinal structures of the mice were removed and studied. Behrend and her research partners found no statistically significant difference between bone growth and development in the titanium group and the control group, leading to a simple conclusion that she displayed in bold during her presentation: MCGRs work.

“The work that my students do — almost all of it is over my head,” Smith said. “It’s new and emerging research. We can’t look it up in a textbook, because it’s not there. They’re discovering it for themselves.”

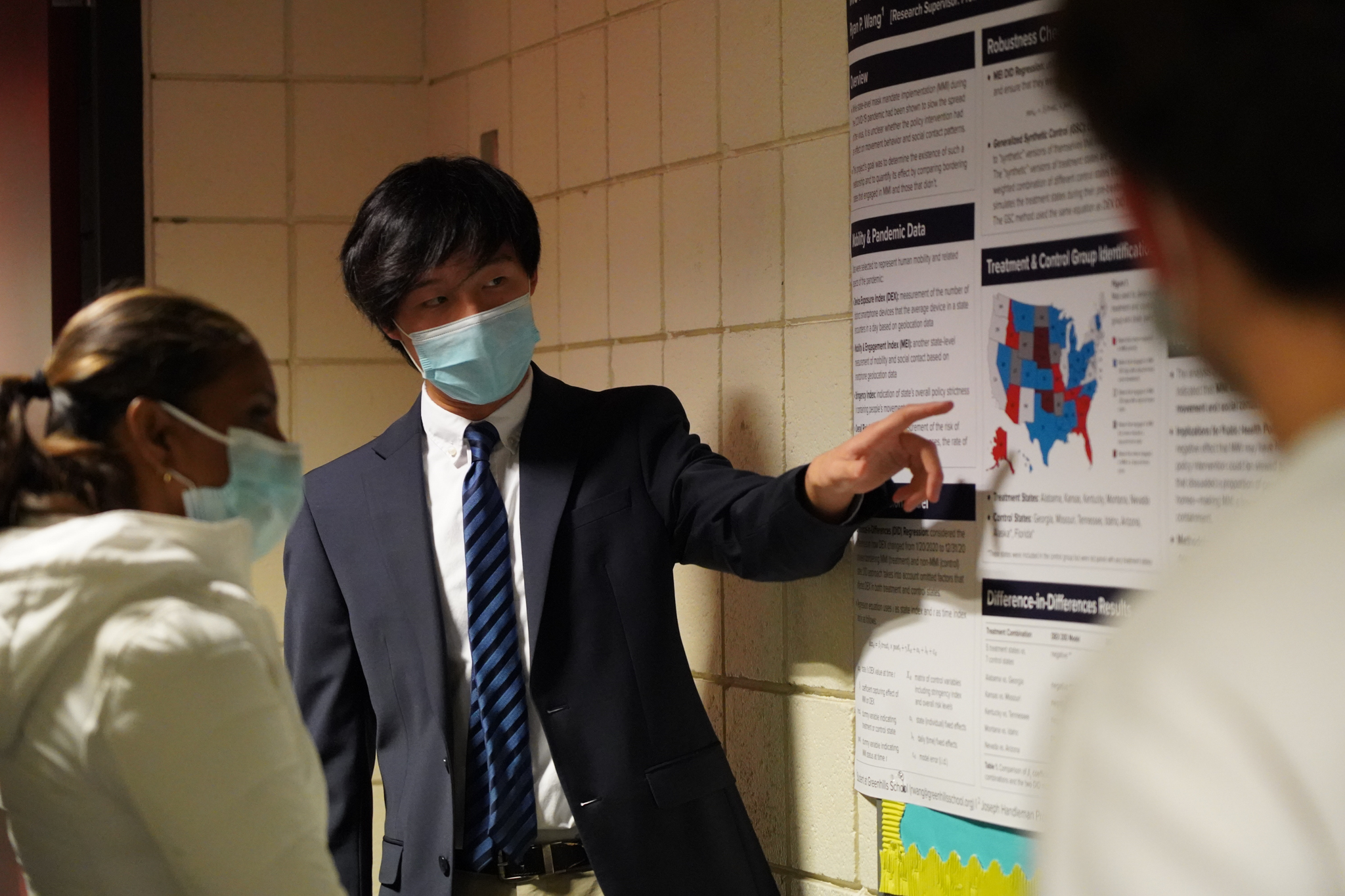

The 34 students who participated in the program conducted all sorts of different research. Rukmini Nallamothu studied gender portrayals in pharmaceutical advertisements. Kilas Gallimore worked to update the equation widely used by traffic engineers to determine the duration of a yellow light. Ryan Wang studied the impacts of mask mandates on human movement and social contact. Abigail Quint used machine learning to detect Microsatellite Instability in Colorectal Cancer patients, and eventually wrote a computer program that achieved a success rate near 100 percent. Ryder Fried studied Twitter use by Major League Baseball teams, and found that while most Twitter metrics have improved since 2019, video tweets, for some reason, have garnered less engagement. Anna Zell studied societal perceptions of violence against native women. Clara Ballard used computer-aided design and a 3D printer to design a pressure barrel in order to automate the delivery of a liquid phase in the manufacture of solar cells.

Regardless of their research area, though, the annual Advanced Research presentations often leave attendees shaking their heads in disbelief that this kind of scientific research was conducted by a group of high school students. It’s certainly not something you see in high school every day.

“This is a program that is very unique to Greenhills School,” Smith said. “It’s one of the things that makes us that ‘one of a kind.’”